Sir CV Raman’s Biography: The first Asian Nobel Prize winner

Introduction

The genius who won the Nobel Prize for Physics, with simple equipment barely worth Rs. 300. He was the first Asian scientist to win the Nobel Prize. He was a man of boundless curiosity and a lively sense of humor. His spirit of inquiry and devotion to science laid the foundations for scientific research in India. And he won the honor as a scientist and affection as a teacher and a man.

One day in 1903, Professor Eliot of Presidency College, Madras, saw a little boy in his B.A. Class.

Thinking that he might have strayed into the room, the Professor asked, “Are you a student of the B.A. class?”

“Yes Sir,” the boy answered.

“Your name?”

“C.V. Raman.”

This little incident made the fourteen-year-old boy well known in the college. The youngster was later to become a world-famous scientist.

A Child Genius

Tiruchirapalli is a town on the banks of the river Cauvery. Chandrasekhara Ayyar was a teacher in a school there. He was a scholar in Physics and Mathematics. He loved music. His wife was Parvathi Ammal. Their second son was born on 7th November 1888. They named the boy Venkata Raman. He was also called Chandrasekhara Venkata Raman or C.V. Raman.

Raman grew up in an atmosphere of music, Sanskrit literature, and Science. He stood first in every class and was talked about as a child genius. He joined the B.A. class of the Presidency College. In the year 1905, he was the only boy who passed in the first class. He won a gold medal, too.

He joined the M.A. class in the same college and chose Physics (the study of matter and energy) as the main subject of study. Love of science, enthusiasm for work and the curiosity to learn new things were natural to Raman. Nature had also given him the power of concentration and intelligence. He used to read more than what was taught in the class. When doubts arose he would set down questions like ‘How?’ ‘Why?’ and ‘Is this true?’ in the margin in the textbooks.

The works of the German scientist Helmhotiz (1821 – 1891) and the English scientist Lord Raleigh (1842 – 1919) on acoustics (the study of sound) influenced Raman. He took immense interest in the study of sound. When he was eighteen years of age, one of his research papers was published in the ‘Philosophical Magazine’ of England. Later another paper was published in the scientific journal ‘Nature’.

Officer – Scientist

Raman’s elder brother C.S. Ayyar was in the ‘Indian Audit and Accounts Service’ (I.A.A.S.).

Raman also wanted to enter the same department. So he sat for the competitive examination.

The day before this examination, the results of the M.A. examination were published. He had passed in first-class recording the highest marks in Madras University up to that time. He stood first in the I.A.A.S. examination also.

On May 6, 1907, Raman married Lokasundari Ammal. At the age of nineteen, Raman held a high post in the government. He was appointed as the Assistant Accountant General in the Finance Department in Calcutta. And the same year something happened to give a new turn to his life.

210, Bow Bazaar Street

One evening Raman was returning from his office in a tramcar. He saw the nameplate of the ‘Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science’ at 210, Bow Bazaar Street. Immediately he got off the tram and went in. Dr. Amritlal Sircar was the Honorary Secretary of the Association. There were spacious rooms and old scientific instruments, which could be used for the demonstration of experiments.

Raman asked whether he could conduct research there in his spare time. Sircar gladly agreed. Raman took up a house adjoining the Association. A door was provided between his house and the laboratory. During the daytime, he would attend his office and carry out his duties. His mornings and nights were devoted to research. This gave him satisfaction. So he continued his ceaseless activities in Calcutta.

From Accounts to Science

At that time Burma and India were under a single government. In 1909, Raman was transferred to Rangoon, the capital of Burma. When Chandrasekhara Ayyar passed away in 1910, Raman came to Madras on six months’ leave.

After completing the last rites, Raman spent the rest of his leave period researching in the Madras University laboratories.

The Science College of Calcutta University was started in 1915.

There a chair for Physics was established in memory of Taraknath Palit, a generous man.

Raman was appointed Professor. He sacrificed the powerful post in the government, which brought a good salary.

The Indian Science Congress was started in 1913. It aimed to bring together scientists engaged in research; they should meet and exchange ideas. Its first session was held in 1914.

Ashutosh Mukherjee was the President. Raman was the President of the Physics section. Later he worked for many years as the Secretary of the Science Congress. He presided over its annual sessions in 1929 and 1948.

Professor Raman

In 1917, at the age of 29, Raman became the Palit Professor. He continued research along with the new assignment.

Raman was very deeply interested in musical instruments such as the Veena, the Violin, the Mridangam, and the Tabala. He began to work on them. Around 1918 he explained the complex vibrations of the strings of musical instruments.

He later found out the characteristic tones emitted by the Mridangam, the Tabala, etc…

Amritlal Sircar, who was devoting all his time to the welfare of the Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science, passed away in 1919.

Professor Raman became its Honorary Secretary.

Two laboratories – those of the College and the Association – were under him, and this gave a new stimulus to his researches. Both his body and his mind could do all the work that had to be done. Many students came to him from different parts of the country for post-graduate studies and research. 210, Bow Bazaar Street and the University Science College Laboratory – these became the active research centers of India. Research workers like Meghnad Saha and S.K. Mitra, who became famous later, worked at these centers.

The Great Teacher

That was a time when Raman was completely immersed in experiments and research.

According to the terms of the Palit Chair, he could have remained free from teaching work, doing research only. But Raman had great pleasure in teaching. Students were inspired by his lectures. They were eager to listen to him. He would not stick to one particular textbook. His lectures brought the fragrance of fresh research.

They reflected Raman’s great curiosity about the secrets of nature. Usually, the lecture was of an hour’s duration. Forgetting the time in the discussion of the subject, Professor Raman would sometimes lecture for two or three hours. Any doubt or question from a student would stimulate new scientific ideas.

Not a Minute to Waste

Absorbed in experiments, it was not unusual for him to forget food and sleep. Sometimes working late at night, he would sleep in the laboratory on one of the tables.

In the mornings too, most of his time was spent in the laboratory. He worked in informal clothes. At 9.30 a.m. he would rush home. After a shave and a bath, he would dress up and send for a taxi. He would finish his breakfast in two or three minutes and get into the taxi. Racing over a distance of four miles, he would reach the class on time. He never wasted time.

In England

The Congress of the Universities of the British Empire met in 1921 in London. Raman went to England as the representative of Calcutta University. This was his first visit abroad.

Raman lectured in the ‘Physical Society’ of London. People came in large numbers to listen to him. He was introduced to J.J. Thomson and Ernest Rutherford, the famous English Physicists.

Raman visited St. Paul’s Church in London. A whisper at one point of the church tower is heard clearly at another point. This effect, produced by the reflection of sound, aroused his curiosity.

The Blue of the Sea

Raman’s journey to England and back was by sea. In his leisure hours, he used to sit on the upper deck of the ship and enjoy the beauty of the vast sea. The deep blue color of the Mediterranean Sea interested the scientist in him. Was the blue due to the reflection of the blue sky? If so, how could it appear in the absence of light?

Even when big waves rolled over the surface, the blue remained. As he thought over the problem, it flashed to him that the blue color might be caused by the scattering of the sun’s light by water molecules. He turned over this idea in his mind again and again. Immediately after his return to Calcutta, he plunged into experiments. Within a month, he prepared a research paper and sent it to the Royal Society of London.

Next year he published a lengthy article on the molecular scattering of light.

Raman never held the wrong belief that research could be carried out only with foreign-made or very complicated equipment. No doubt, he imported some equipment. But he prepared much of the equipment he used with the help of his students.

New Contacts

Scientists of many countries appreciated the research papers of Raman and his colleagues.

The Royal Society, the oldest and the most important scientific society of England, honored Raman in 1924 by electing his as its ‘Fellow’ (that is, a member).

The annual session of ‘The British Association for the Cultivation of Science’ was held in the same year in Toronto (Canada). Raman inaugurated the seminar on the scattering of light. R.A. Millikan, the famous American Physicist, who also attended, was full of admiration for Raman.

They became fast friends too.

At the Mount Wilson Observatory in California (U.S.A), a telescope of 100-inch width was in use.

Those were the times when discoveries in the field of astronomy (the study of stars and planets and their movements) filled people with wonder.

Raman was always eager to learn new things.

He spent a couple of days on Mount Wilson.

During the nights he viewed the Nebula (a bright or dark patch in the sky caused by distant stars or a cloud of gas or dust.) through the telescope and was thrilled.

He went to Russia in 1925 to participate in the two hundredth anniversary of the ‘Russian Academy of Sciences’.

The Guide

Many scholars were working in the Calcutta laboratories to unlock the secrets of sound and light. To all of them, Professor Raman was the

‘Guru’ and the leader. He had observed the blue color of the deep glaciers (mass of ice or snow) in the Alps mountain ranges. Taking the clue from this, some of the research workers studied some scattering of light in ice and quartz crystals. They also studied the scattering of light in liquids such as pure water and alcohol, as well as in vapors and gases.

With a complete mental picture of the phenomenon, Raman would proceed to experiment systematically. After that, he would write the research paper based on the results of the experiments and arrange for its early publication. Sometimes it would be late in the day by the time the final copy was prepared. Then he would rush to the General Post Office in a taxi to catch the last mail. Then he would enjoy a feast of Rasagulla with his students.

He started ‘The Indian Journal of Physics’ in 1926 to make the prompt publication of research papers possible.

Raman wanted the young men working with him to take up independent positions and to serve the nation. He felt that his laboratory was a center of training for young talent, but not a permanent storehouse.

Raman’s research on sound became famous all over the world. ‘Handbuck der Physic’, a German Encyclopedia of Physics, was published in 1927. Raman was the only foreign scientist invited to contribute an article to it.

Raman Effect

Sometimes a rainbow appears and delights our eyes. We see in its shades of red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo and violet. The white ray of the sun includes all these colors. When a beam of sunlight is passed through a glass prism a patch of these color- bands are seen. This is called the spectrum. The Spectrometer is an apparatus used to study the spectrum. Spectral lines in it are characteristic of the light passing through the prism. A beam of light that causes a single spectral line is said to be monochromatic.

When a beam of monochromatic light passes through a transparent substance (a substance that allows light to pass through it), the beam is scattered. Raman spent a long time in the study of the scattered light. On February 28, 1928, he observed two low-intensity spectral lines corresponding to the incident monochromatic light. Years of his labor had borne fruit. It was clear that though the incident light was monochromatic, the scattered light due to it was not monochromatic. Thus Raman’s experiments discovered a phenomenon that was lying hidden in nature.

The 16th of March 1928 is a memorable day in the history of science. On that day a meeting was held under the joint auspices of the South Indian Science Association and the Science Club of Central College, Bangalore; Raman was the Chief Guest. He announced the new phenomenon discovered by him to the world. He also acknowledged with affection the assistance given by K.S. Krishnan and Venkateshwaran, who were his students.

The phenomenon attracted the attention of research workers all over the world. It became famous as the ‘Raman Effect’. The spectral lines in the scattered light were known as ‘Raman Lines’.

Is light wave-like or particle-like? This question has been discussed from time to time by scientists. The Raman Effect confirmed that light was made up of particles known as ‘photons’. It helped in the study of the molecular and crystal structures of different substances.

World-Wide Interest in Raman Effect

Investigations making use of the Raman Effect began in many countries. During the first twelve years after its discovery, about 1800 research papers were published on various aspects of it and about 2500 chemical compounds were studied. Raman Effect was highly praised as one of the greatest discoveries of the third decade of this century.

After the ‘lasers’ (devices that produce intense beams of light, their name coming from the initial letters of ‘Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation) came into use in the 1960s, it became easier to get monochromatic light of very high intensity for experiments. This brought back scientific interest in Raman Effect, and the interest remains alive to this day.

The World Honors Raman

Raman received many honors from all over the world for his achievement. In 1928 the Science Society of Rome awarded the Matteucci Medal.

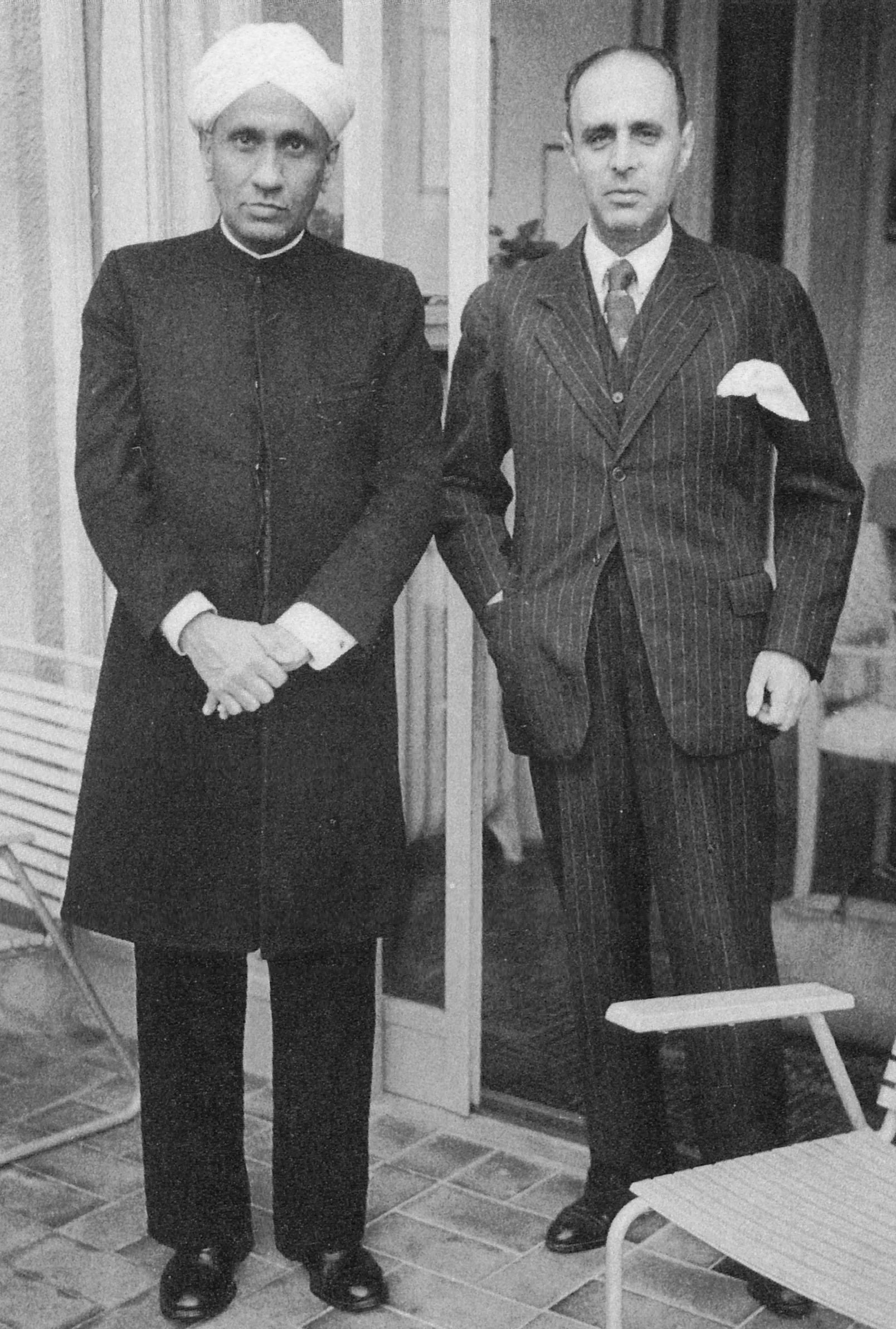

In 1929 the British Government knighted him; thereafter Professor Raman came to be known as Professor Sir C.V. Raman. The Royal Society of London awarded the Hughes Medal in 1930.

Honorary doctorate degrees were awarded by the Universities of Freiburg (Germany), Glasgow (England), Paris (France), and Bombay, Benaras, Dacca, Patna, Mysore, and several others.

The Nobel Prize, Too

The highest award a scientist or a writer can get is the Nobel Prize. In 1930, the Swedish Academy of Sciences chose Raman to receive the Nobel Prize for Physics. No Indian and no Asian had received the Nobel Prize for Physics up to that time. At the ceremony for the award, Raman used alcohol to demonstrate the Raman Effect.

Later in the evening, alcoholic drinks were served at the dinner. But Raman did not touch them. He remained loyal to the Indian traditions.

A Keen Eye

However minute the results of an experiment, they could not escape the searching eyes of Raman. And his mind retained every detail of what he observed. An incident, which took place at Walter, the seat of Andhra University, may be mentioned. After the discovery of the Raman Effect, spectra of different substances were being studied there. On one of his visits there, Raman found the research workers puzzled at not getting the expected spectral lines. Raman examined the plate containing the spectrum and exclaimed with joy, “There it is, you see!” He immediately got a projector and made the weak spectral lines visible on the white screen.

In Bangalore

He came to Bangalore as the Director of the Tata Institute (the Indian Institute of Science) in 1933. The Tata Institute soon became famous for the study of crystals. The diffraction of light (the very slight bending of light around corners) by ultrasonic waves (high-frequency sound waves which we cannot hear) in a liquid was elegantly explained by Raman and Nagendranath. This became known as the ‘Raman-Nath Theory’.

Raman’s Day

Raman was an early riser and used to take morning walks regularly. The sight of tall trees against the sky at dawn delighted him. By six in the morning, he would be in the chamber where he worked. Up to 9 a.m., he would devote his time to discuss with students who were experimenting and to the study of research papers.

At 10 o’clock he would be in the Director’s office.

He would complete the office work and return to the laboratory. He would be immersed in research until 8.30 p.m. He used to arrange two or three seminars every week. At these seminars, all the workers would come together to discuss various problems of their research.

‘Use a 10-Kilowatt Brain’

Whenever students showed new results, Raman was delighted. He would guide them to do further work. If they appeared to be depressed he would inspire them to fresh efforts.

A student was once experimenting with an X-ray tube of one-kilowatt power. He learned that a scientist in England was experimenting on the same problem with a five-kilowatt X-ray tube, and grew depressed. When Raman, who was on his rounds, came to know of this, he said with a smile, “There is a very simple solution; use a 10-kilowatt brain on the problem.” Raman possessed supreme self-confidence and he generated it in his students also. Raman used to enquire about his students even after they left his Institute. If they had any difficulty he would help them as best he could.

Judging Talent

Raman had his method of judging the merit of a student. Once he set a question concerning the vibrations of the Mridangam at the Post-Graduate Examination of the Allahabad University. This was different from the other questions based on textbooks. Only one student answered it and he had spent all the allotted time on this one answer. Raman was pleased with his talent and personally congratulated him.

Once a candidate attended an interview for a research post in the Tata Institute. He had passed in the first class. He was asked, “Are there any scientific problems you would like to work on?” There was no satisfactory answer. Physically also the candidate was weak. Raman advised him,

“Research is a strange work. Success in it brings limitless joy whereas failure pushes one to deep despair. Joy and despair – both require bodily strength. You should first improve your bodily strength through sports and exercises.”

The Indian Academy of Sciences

To encourage scientific research in India, Raman established the Indian Academy of Sciences in 1934. From that year the science journal ‘The Proceedings of the Academy’ is being published every month.

The Government of Mysore granted 24 acres of land to promote the activities of the Academy. It was his earnest desire ‘to bring into existence a center of scientific research worthy of our ancient country, where the keenest intellectuals of our land can probe into the mysteries of the Universe’. He fulfilled his wish by establishing a Research Institute at Hebbal, Bangalore. He did not seek help from the Government but gave away all his property to the Institute. The Executive Committee of the Academy named the center ‘Raman Research Institute’.

The Raman Research Institute

In 1948 this great scientist entered one more active phase of life when he became the Director of the Raman Research Institute. The Institute became the center of all his activities.

A garden and tall eucalyptus trees surrounded it. He used to say, “A Hindu is required to go to the forest in old age, but instead of going to the forest, I made the forest come to me.” At the Institute he could concentrate on things that interested him. He was alone with his work and was happy. At the entrance to the Institute was a board bearing the words, “The Institute is not open to visitors. Please do not disturb US.” He researched sound, light, rocks, gems, birds, insects, butterflies, seashells, trees, flowers, atmosphere, weather and physiology of vision and hearing. His study covered such different fields of science like Physics, Geology, Biology, and Physiology. Among them sound and colors particularly attracted him. Once he even went around shops to select sarees of different color designs.

Delight in Color and Light Raman collected rocks and precious stones.

His invaluable collection included hundreds of objects such as sand that melted due to lightning, rock indicating the lava flow during a volcano and diamonds, rubies and sapphires. Many fluorescent minerals (that is, minerals having the property of receiving short invisible rays and sending out long visible rays) were kept in a dark room. There he could create a small twinkling world by switching on the ultra-violet light. Thin layers of some crystals were prepared for study.

No color was seen when they were viewed perpendicularly. But the viewer had only to change the angle – and blue, green and yellow colors delighted the eye. After a deep study of diamonds, Raman explained many of their characteristics.

Once in Paris, he went shopping for diamonds and crystals. There two beautiful butterflies with blue wings in a shop window attracted him. He bought them and later collected thousands of specimens.

Raman loved flowers for their colors. He grew many flower plants. He used to visit flower exhibitions to examine flowers.

Raman used to announce his new scientific discoveries at the annual sessions of the Academy. At the Madras session (1967) he discussed the influence of the earth’s rotation on its gaseous envelope. Next year he put forward his theory of the physiology of vision.

Many countries and institutions continued to honor him. The membership of the American Optical Society (1941), the National Professor-ship of India (1948), the Franklin Medal of the Franklin Institute (1951), the International Lenin Prize (1957), the Membership of the Pontifical Academy of Science (1961) -these were some of the honors conferred on him.

The greatest honor the Government of India confers on an Indian is the award of ‘Bharat Ratna’. Raman became a ‘Bharat Ratna’ in 1954.

Interest in Music

Raman was a great lover of music. He used to say, “I should live long because I have not heard all the music I want to hear.” He was a frequent visitor to a shop selling musical instruments in Balepet, in Bangalore. He collected a variety of musical instruments like the Mridangam, the Tabla, the Veena, the Violin, and the Nadaswaram.

‘The Catgut Acoustical Society’ of America is devoted exclusively to the study of violins. It elected Raman as its honorary member.

‘A General Practitioner in Science’

When Raman stepped into the field of research, Modern Physics was in its infancy. It developed numerous branches by the time he began working in his own Institute. Then research workers had access to modern equipment and methods, which were not available six decades earlier.

They tended to study a small field and to specialize in it. But Raman never limited his activities and interests to a narrow field.

Raman once inaugurated the ‘General Practitioners’ Conference’ in Bangalore. A general practitioner is a doctor who treats common illnesses. Raman humorously commented on that occasion that he was a general practitioner in science. He liked all scientific problems whether they were small or big. His interest and satisfaction lay in finding a solution to the problem.

In 1969, the daughter of Nagendranath (who had been a research student under him thirty years earlier) was married; Raman and his wife attended the reception. Raman drew Nagendranath aside and explained his new problem; he was trying to find a theory of earthquakes taking into account the actual shape of the earth and the wave-like nature of the quakes. Raman was not a person to be satisfied with his past achievements. He was always seeking new and vaster fields of study.

Raman was a delightful speaker. Sprinkled with good humor, his talk was usually focused on realities. Raman used to say that the color of the sea interested him more than the fish, which lived in it. He thought that we should have our ships for oceanographic research (the study of the sea). He often said that India lost her freedom because she took no interest in the seas.

A Lion’s Heart

Friends and admirers organized a special function at the Annual Session of the Academy at Ahmedabad to honor him on his eightieth birthday. Many people expressed warm sentiments. Raman never took much interest in birthday celebrations. Still, at the end. He thanked the organizers; and with a twinkle in his eyes, he said, “I wish someone had said that I had a lion’s heart!” All who had spoken forgot to make mention of his great asset, namely courage.

The True Research Student

Raman was studious. He kept in touch with the latest developments in science in the world around him. He had personal contact with many scientists. He used to read new books and research papers from different centers. On one occasion he was addressing the students of Presidency College, Madras. Like an elder brother, he told them,

“How much can you learn in an hour’s lecture? Spend more time in the library.”

Studying and experimenting, he remained a student throughout his life.

“The equipment which brought me the Nobel Prize did not cost more than three hundred rupees. A table drawer can hold all my research equipment,”

he used to say with pride. It was his conviction that if the research worker is not inspired from within, no amount of money can bring success in research.

He hoped that scientists of free India would win worldwide fame by their discoveries. “If there are no facilities here, what is wrong with their going abroad and spreading the fame of India?

Did not the workers of the East India Company come and rule India?” he used to say.

Raman was not conservative in his outlook.

He used to spell out his opinions boldly. When he was called ‘India’s illustrious scientist’ he would correct the description with humility: “I am just a man of science.” When scientists were criticized he would retort with confidence that they were the salt of the earth.

His God and His Religion

Raman would not speak much about God and religion. Science was his God and works his religion. He believed that discoveries confirm the existence of God; if there is God we have to find Him in this universe.

A journalist once asked him, “What do you feel about the long and eventful period of your scientific work and achievements?” Raman replied promptly,

“I have no time to think of the past and I am not inclined to do so. I spend my life as a scientist. My work gives me satisfaction.”

As he was completing his 82 year Raman organized a weeklong conference of the members of the Academy in September 1970. On that occasion, he invited young scientists to present papers on different subjects.

Every year he used to deliver a popular science lecture on Gandhi Jayanthi Day. In 1970, he spoke on the new theories about hearing and the eardrum. This was his last lecture.

A few days before his 83rd birthday Raman suffered a mild heart attack. But there was a quick recovery. He never dreamt of a life without work.

He had told his doctor, “I wish to live a hundred-per-cent active and fruitful life.” Raman, a seeker of truth throughout his life, passed away on the 21st of November 1970.

Radhakrishnan, his younger son, became the Director of the Raman Research Institute.

Without much encouragement, Raman had entered the field of science in his early years.

Deeply attracted by the secrets of sound and light, he marched ahead in the world of science. By his achievements and self-respect, he earned an honored place for India in the world of science. He laid the foundations of a scientific tradition in India by building up institutes for research, by publishing science journals and by encouraging young scientists. Truly he was the ‘Grand Old Man of Indian Science’.

Raman possessed the curiosity of a little boy to know new things and the intuition of a great genius in understanding the secrets of Nature.

The life of this great scientist was truly the life of a great seer.